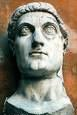

Who was Constantine? Constantine (280?-337) was the first Christian emperor of Rome. Constantine had ruled jointly with Maxentius for a while, until Maxentius tried to take over. Constantine marched his much smaller force to meet Maxentius at the Tiber about 10 miles north of Rome. Aware of the occult connections of his foe, Constantine asked for Divine help. It was then that he saw a cross in the sky with the words, “In this sign conquer.” The Battle of Milvian Bridge, fought on October 28, 312, was furious, but Constantine won. The next year he issued the Edict of Milan, which halted persecution of the church. In a dramatic about-face, Constantine adopted Christianity as the religion of the Empire. He personally professed faith, but refused baptism until on his deathbed. Whatever his faults, his life on balance marked a stride forward for Christianity.

Historical context. Ten official persecutions of Christians marked the period from Augustus to Constantine. The blood of the martyrs was the seed of the church. Finally, the victory of Constantine at Milvian Bridge (312 A.D.) resulted in the Edict of Milan (313 A. D.) and the end of persecution. Christianity became the religion of the Empire. In 330 Constantine founded Constantinople (or Byzantium). It remained capitol of the Eastern Empire until 1453. This was a period of more than a thousand years unrivaled in history for its stability. This was largely because of its anti-inflationary gold coinage. It was not long after the coinage was debased that Byzantium fell.

Summary of Constantine’s teaching. The early church was plagued by heresy. Doctrine became clearer as the heresy was refuted. At this juncture the church was wrapped up in the Arian problem. Arias claimed that Christ was merely a created being. Athanasius opposed Arias’ teaching. He claimed that Christ was of the same substance with God, not just like substance. Wishing to maintain peace and unity in the empire, Constantine called the Council of Nicea. He hoped to produce a meeting of minds. Constantine did not preside at the Council, but used his civil power to enforce the Orthodox position. At Nicea Christ was declared to be “…GOD of GOD, begotten, not made, being of the same substance with the Father….”

Implications for subsequent history. The outcome of Nicea (325) was of great import as a statement of the deity of Christ. However, Constantine may have assumed an unbiblical authority in taking part in it. This was close to the old Roman policy of requiring subject people to bow to the religious priority of the state. This precedent was the source of church-state bickering for hundreds of years.

For instance, even a Christian prince as wise as Charlamagne in 9th Century France had assumed power to appoint bishops. He set up a study group/seminary in his courtroom with Bible scholars from all over Europe. Each assumed a Bible nickname, Charles himself being King David. Each day after the hunt, they would sit and discuss the Bible and the classics. These men were given bishoprics in outlying areas. There they set up their own schools to train other bishops. Charlamagne used his power to appoint bishops wisely, but most later Emperors did not. In some cases they sold the bishoprics to the highest bidder. They were prized for the land holdings attached to them. Thus did Charlamagne become the founder of the Holy Roman Empire. It lasted over 1,000 years until dissolved by Francis II in 1806. This Empire started when Pope Leo crowned Charlamagne as he knelt before the altar in the year 800. It thus became a custom for the pope to anoint the new Emperor. This ceremony offset the secular abuse to some extent.

After Gregory VII and the Papal Revolution in 1075, the power to appoint bishops was given to the Pope. The state went its own way into the secular realm. During the Investiture Struggle (1075-1122) Gregory denied the power of the civil ruler to invest bishops with office. The Bible grants the local congregation power to select church leaders (Acts 6:3), who are then appointed by existing church leaders. The civil ruler is not involved.

Biblical analysis. A biblical understanding of the separation of church and state sees the two institutions as working together. However, they have distinct roles directly under God. The church’s role is evangelism and discipleship, leading men and nations to the worship of God. For its part the state is to ensure justice according to the law of God. This creates peace and freedom in which men and church may fulfill their callings under God. The Bible forbids either church or state assuming the duties of the other. For instance, King Uzziah was given leprosy for presuming to offer the sacrifice (II Chron. 26:18-21). Saul was also judged for this offense (I Sam 13:12-14).

Corrective or prescriptive actions. A faulty concept of separation of church and state has plagued the world to the present day. In the modern world the church is seen as useless. She has only herself to blame. She is merely reaping the reward of her neo-Platonic, otherworldly theology. Church leaders must take the lead in making friends with civil leaders. They must teach them the law of God and counsel them about how it applies to criminal justice.