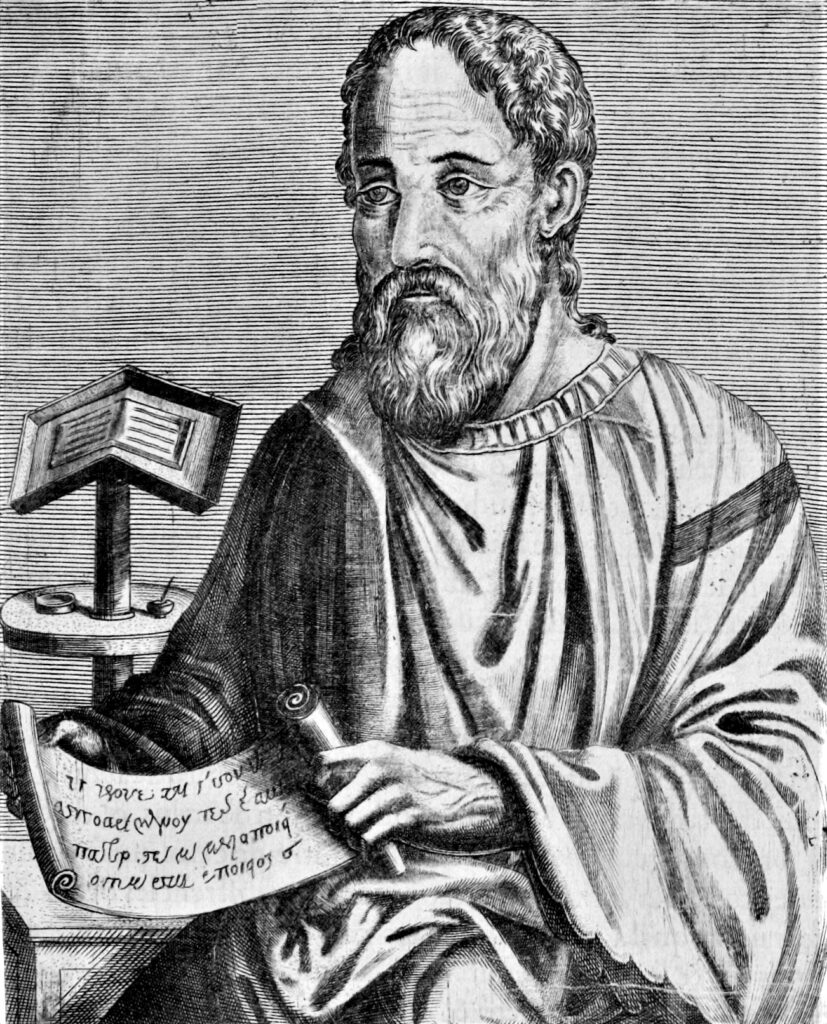

Who was Eusebius? (260-340) Eusebius was the Bishop of Caesarea on the eastern Mediterranean. He is known as “The Father of Church History” and without him much of what we know about the early church would have been lost. He wrote The History of the Church, covering the first three centuries of the Christian era until 324 A.D. Eusebius was not a great writer in the classical sense, but he was prolific, accurate, and possessed of a deep love for transmitting historical information.

Historical context. Eusebius, like many other of the early church fathers, not only summoned Christians to obedience to the civil magistrate, but also summoned the magistrate to obedience to God. During the first three centuries, 10 Imperial persecutions had been inflicted on the church. The emperor Constantine answered the call to obedience prior to the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (312) when he saw a flaming cross in the sky and the words “In this sign conquer.” Constantine went on to miraculously defeat his evil rival, Maxentius, and issued the Edict of Milan, embracing Christianity as the state religion and halting the persecution of Christians. Eusebius, who came to be highly regarded by Constantine, interpreted this to be an aspect of God’s promise that kings would flow from Abraham.

Summary of Eusebius’ teaching. Eusebius was eyewitness to, and records many of the persecutions of the early church and the testimony of the martyrs. Notable among these was Polycarp, a personal disciple of the Apostle John. Apprehended and dragged into the arena, the proconsul tried to persuade him to deny Christ: “Swear, and I will set you free: execrate Christ” (1) “For eighty-six years,” replied Polycarp, “I have been His servant, and He has never done me wrong: how can I blaspheme my King who saved me?” When bound at the stake, the fire took the shape of a vaulted room and would not consume him; finally, a sword was required to extinguish his life. In total, Eusebius tells the story of 146 martyrs and 47 heretics who plagued the church in the period leading up to the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD.

As the “Father of Church History”, Eusebius rejected what is today known as the premillennial interpretation of prophecy. Referring to Papias, he dismissed it as a misinterpretation: “He says that after the resurrection of the dead there will be a period of a thousand years, when Christ’s kingdom will be set up on this earth in material form. I suppose he got these notions by misinterpreting the apostolic accounts and failing to grasp what they had said in mystic and symbolic language. For he seems to have been a man of very small intelligence, to judge from his books. but it is partly due to him that the great majority of churchmen after him took the same view….” (2)

Eusebius also discounted that doctrine of the Holy Spirit that today goes by the name of “charismatic” or “Pentecostal.” This doctrine was being promoted by a recent convert known as Montanus, who “was filled with spiritual excitement and suddenly fell into a kind of trance and unnatural ecstasy. He raved, and began to chatter and talk nonsense, prophesying in a way that conflicted with the practice of the Church handed down generation by generation from the beginning…They cannot point to a single one of the prophets under either the Old Covenant or the New who was moved by the Spirit in this way….” (3). Eusebius’ report would tend to discount attempts by modern “charismatics” to trace their origins to the giving of the Holy Spirit recorded in Acts 2.

Yet Eusebius was not without his own doctrinal distortions. He delivered the opening address at the Council of Nicaea, which settled the great issues regarding the nature of Christ as both God and man. He became the leader of the “Semi-Arian” party, which shied from discussing the nature of the Trinity. However, he sided with the Athanasian position in the end: Christ was of the same essence, not just of like essence with the father. He exhibited Arian tendencies in subsequent synods of the church, which accounted in part for his popularity with Constantine. Constantine was very respectful and compassionate toward the church, but he still regarded the church as a department of state, with himself its ultimate head. Eusebius tended toward this position as well (4).

Implications for subsequent history. We are indebted to Eusebius for our understanding of God’s working in and through the church subsequent to the Book of Acts. However, Eusebius had a negative influence on Augustine in two respects. One was his tendency to Platonize and allegorize the Bible and the other was his evidential apologetic for Christianity based on its positive impact on history. The problem with the historical apologetic is that it can be a two-edged sword when history begins to flow in more tempestuous channels. Augustine learned this lesson the hard way when Christianity was blamed for the fall of the Roman Empire.

Biblical analysis. The History of the Church records the fulfillment of Jesus’ promise that “if they have persecuted me, they will also persecute you” (Jn. 15:20). We cannot read the lives of the martyrs or hear stories of modern-day martyrs in places like the Sudan and China without being challenged in the depth of our soul. We must pray for them and for ourselves a spirit of endurance, faith and rejoicing, “inasmuch as ye are partakers of Christ’s sufferings; that, when his glory shall be revealed ye may be glad also with exceeding joy” (I Peter 4:13).

In spite of persecutions and heretics, Eusebius believed that in Constantine and the Edict of Milan he was seeing the fulfillment of the Messianic kingdom prophecies in his own day. For example, he quoted Psalm 46:8,9 in this regard: “He maketh wars to cease unto the end of the earth; he breaketh the bow, and cutteth the spear in sunder…Be still and know that I am God: I will be exalted among the heathen….” Thus, he was postmillennial in his eschatological outlook. The blood of the martyrs was indeed the seed of the church.

Corrective or Prescriptive Actions. Though the course of history will ebb and flow and the church will fall in and out of favor with the civil authority we must, like Eusebius, always remain optimistic. Based on the promises and prophecies of God, he knew that the church would be increasingly victorious as history progressed, even if it seems like two steps forward and one step back.