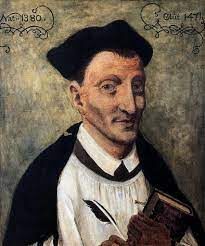

Who was Thomas a Kempis? (1380-1471) Thomas a Kempis was a German monk and compiler of the highly influential devotional book, The Imitation of Christ.

Historical context. William Griffin described the 14th Century in this fashion in his contemporary translation of The Imitation of Christ: “Flamboyant traceries were lightening the interiors of those Gothic blockhouses called cathedrals. Castles were abuilding, but not without battlements. Crusaders were afoot and a danger to themselves as well as to others, especially to the infidels, who by this time were on the run. Knighthood was in flower, albeit out to deflower much of the maidenhood of Christendom. Rumor had it that the heavily armored Europeans had already defoliated much of the Holy Land. England exported wool; the Netherlands imported wool and made all sorts of textured textiles, exporting them to the rest of the clothed world, leaving the merchant class back at home to wive it wealthily. And, oh yes! Death came aknocking. The Black Death, appearing as both bubonic and pneumonic plague from 1348 to 1350, killed one-third of the population… Then there was the Hundred Years’ War in France, from roughly 1337 to 1453, ‘an epic of brutality and bravery checkered by disgrace,” as one historian called it. Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales and Baccaccio’s Decameron flooded the market with brief entertainments in a variety of literary styles” (1).

Thomas a Kempis was a leader of the semi-monastic movement in the Netherlands called the “Brethren of the Common Life”, organized in opposition to the spirit of secularism common to this age. This movement was a religious contingent of the neo-Platonic revival that re-emerged near the close of the Renaissance. The order was founded by Gerhard Groote and it seems likely that the book was written by him and his chief disciple, Florentius Radewin before 1384, then compiled by a Kempis about 1429.

Summary of a Kempis’ teaching. There may be nuggets of truth scattered through the Imitation, but it is so laced with error that it cannot be recommended to the serious Christian. One of the best-selling books of all time, the Imitation presents the monastic model as the apotheosis of the Christian life. It is in fact a handbook for life in a monastery, which detracts from the Reformation truth that each believer is a “priest” in the faithful execution of his everyday calling. It promotes Mariology, the Mass , Purgatory and the Apocryphal writings, which places it, of course, squarely in the Roman Catholic tradition. It promotes asceticism and mysticism, both of which are condemned by the Bible. A favorite innovation of the Roman Catholics, Purgatory is an intermediate state of temporary suffering described in the spurious works of the Apocrypha.

In the final analysis, the book is a treatise on Roman Catholic “works salvation” that produces unnecessary guilt in the life of the Christian. The essential message is reform your life in order to avoid Hell: “We’re on the near side of death now, but on the far side await the pains of Hell or Purgatory. Weigh that in your heart, and maybe now you’ll be willing to undertake the laborious program of reform, readying yourself for the Final Rigor” (p. 39) ) The book contains very little of the grace of Christ or His substitutionary sacrifice for the sins of mankind. It is the good works of man, not the work of Christ, that we must bring in our own defense at the day of judgment: “On the Day of Judgment you’ll need to bring papers, proof of all the stuff you did. Why? Well, you’ll have to defend yourself; no defense counsel here” (p. 47). This, of course, defies Paul’s declaration that “not by works of righteousness that we have done, but according to His mercy He saved us, by the washing of regeneration, and renewing of the Holy Ghost” (Titus 3:5).

The Christian reader who remains constantly alert to the prevailing spirit of asceticism that pervades the work may be able to glean some profitable instruction from the Imitation. For example, the book sings of love: “Enlarge Thou me in love, that with the inward palate of my heart I may taste how sweet it is to love and to be dissolved and as it were to bathe myself in Thy love….”(III,6). The call to meditation is one that speaks to modern man in the busyness of life: “…In silence and in stillness, a religious soul advantageth herself, and learneth the mysteries of Holy Scripture. Shut the door upon thee, and call upon Jesus thy Beloved. Stay with him in thy closet; for thou shalt not find so great peace anywhere else (I,20). Other nuggets include, “Man proposes, but God disposes” (Ib. 19), and “Be not angry that you cannot make others as you wish them to be, since you cannot make yourself as you wish to be” (Ib. 16).

Implications for subsequent history. At the time of his death, Groote had applied to the Pope for official recognition of the Brethren as the Order of St. Augustine and their teaching arm was assumed by the Jesuits at the time of the Counter-Reformation, a century and a half later. The Jesuits were the missionary arm of the Papacy’s efforts to reform Catholic morals. Simultaneously, this movement worked to suppress the Reformation via its ersatz pietism, while leaving the door to cultural dominion wide open for the secularists via its hermitic seclusion. Moreover, the work contributed not a little to the supposed Christian ideal of “sanctified ignorance” that has plagued Christianity to the present day: “Learned arguments do not make a man holy and righteous, whereas a good life makes him dear to God.” Such half-truths ignore the fact that orthopraxy (sound practice) is based on orthodoxy (sound knowledge).

Biblical analysis. Mysticism is by definition “seeking by contemplation and self-surrender to obtain unity with or absorption into the Deity or ultimate reality, or the spiritual apprehension of truths that are beyond understanding.” Related to this is asceticism, the “practice of severe self-discipline and abstinence from pleasure, esp. for religious or spiritual reasons”(3). The biblical evaluation of these movements is found at Col. 2:21, “If then you have died with Christ to the elementary principles of the world, why, as if you were living in the world, do you submit yourself to decrees, such as, “Do not handle, do not taste, do not touch!”…in accordance with the commandments and teachings of men? These are matters which have to be sure, the appearance of wisdom in self-made religion and self-abasement and severe treatment of the body, but are of no value against fleshly indulgence” (N.A.S).

The danger of a devotional book such as Imitation of Christ is that it can easily become a substitute for the specific biblical content of the law of God. There are precious few references in the Imitation of Christ to Deuteronomy (2nd law), which was incidentally Christ’s most frequently quoted book. The Imitation is essentially antinomian, pointing men to an inward subjective voice, while neglecting the objective standards of the law of God. As Jesus rebuked the Pharisees, “Howbeit in vain do they worship me, teaching for doctrines the commandments of men. For laying aside the commandment of God, ye hold the tradition of men, … “ (Mk. 7:7,8).

Corrective or Prescriptive Actions: Rather than confronting the world with the claims of Christ and the law of God, mysticism retreats into a Platonic cloister. In Jesus final high-priestly prayer for His followers, He asked “not that thou shouldest take them out of the world, but that thou shouldest keep them from the evil.” (Jn. 17:15). Rather than “advancing to the rear”, Christians must press the attack in every cultural realm.