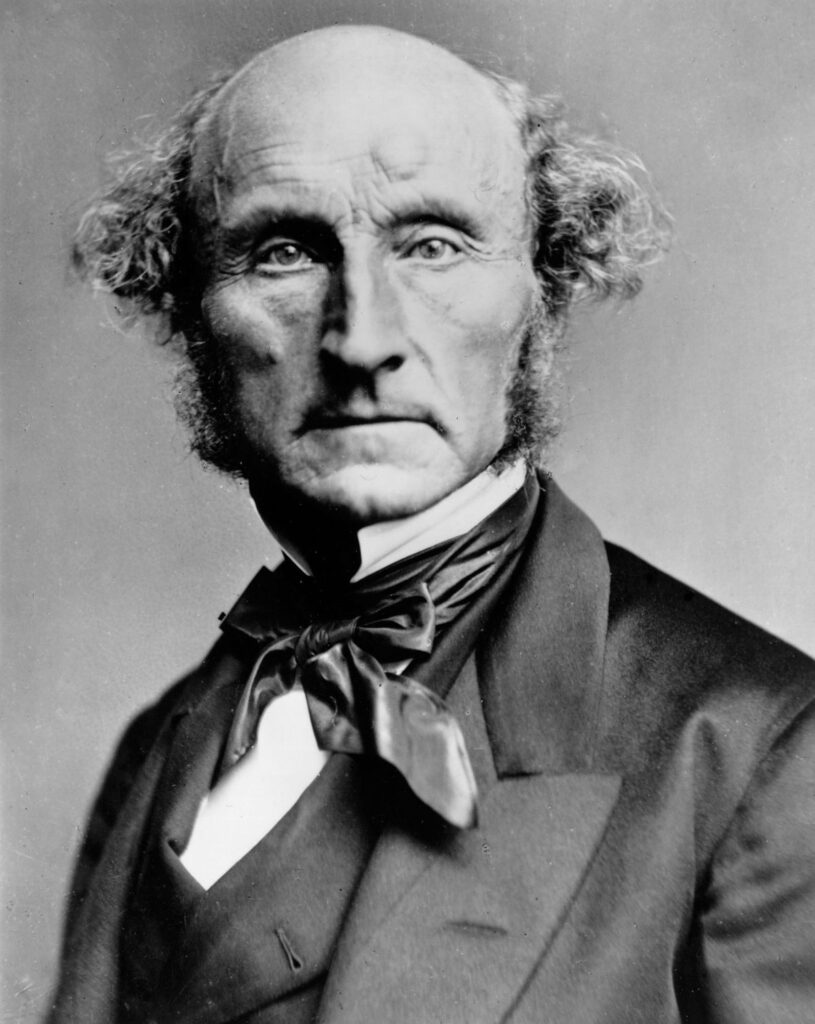

Who was John Stuart Mill? (1806-1873) John Stuart Mill was a British political and economic philosopher, whose work gave major impetus to the development of 19th century utilitarianism.

Historical context. John Stuart Mill’s productive period occurred during the reign of Queen Victoria. The longest of any English monarch, it extended 63 years from, 1837 to 1901. During this era the British colonial empire reached its greatest extent, including Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and many countries of Africa. Victoria was concerned that the Empire be viewed with respect and that it set an example of morality, economic stability and civilization for indigenous peoples. However, she cast a jaundiced eye on many of the changes ushered in by the Romantic era, including government education and extension of the franchise. These were among the changes popularized by John Stuart Mill through his writing and through his brief term (3 years) in Parliament. Thus, the surface tranquility of the long and popular reign of Victoria actually encompassed many profound changes.

These included shifts in the philosophical foundation of British society. Jeremy Bentham in arguing for policies promoting “the greatest good for the greatest number” provided the spade work for the Great Reform of 1832. This was a renovation of criminal law and administrative procedure that transferred power from the landed aristocracy to the creative and entrepreneurial “gentlemen” of the middle class. Mill and his father played an active role in this reform. Similar Democratic movements were afoot in America under Andrew Jackson, in France under Louis Phillipe, and in Russia.

As the middle class took root and prospered there emerged a simultaneous demand for socialistic equality by the lower classes. The genuine abuses of the era were exposed in the works of Charles Dickens, but the bitterness and envy aroused by these abuses was often channeled into counterproductive byways. Ironically, the populist movement utilized many of the same utilitarian arguments employed by the middle class against the aristocracy. John Stuart Mill was a transitional figure caught between the Fabian reforms of the latter part of the century and the earlier Benthamite reforms. Fabius was a Roman general who conquered gradually; his name was later adopted for that socialist doctrine which gradually insinuates itself into a free society. There was a shift in Mill’s thinking after the Great Reform of 1832 based on Tocqueville’s mixed review of American democracy. This accounts for the ambiguity and contradiction often found in his writing.

Summary of Mill’s teaching. Mill rejected the hedonistic, Benthamite theory of “the greatest happiness of the greatest number” as the touchstone for government policy. In his 1863 Utilitarianism, he spoke of happiness as qualitative rather than quantitative, and derived indirectly, rather than by direct government action. In the place of Bentham’s dictum, Mill substituted what he called a “very simple principle”: The individual is free to act except where his actions are contrary to the general interest. In the words of Mill, “The sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection.” Thus, he was a universalistic utilitarian because he took other people into consideration in judging the morality of an act.

A large part of Mill’s On Liberty (1859) is taken up with an analysis of the liberty of thought and free speech. This includes a valuable discussion of the need for truth to be challenged in order to manifest itself as truth, but it approaches at points the Hegelian synthesis. For example, Mill speaks of “a commoner case…when the conflicting doctrines, instead of being one true and the other false, share the truth between them, and the nonconforming opinion is needed to supply the remainder of the truth of which the received doctrine embodies only a part”(1). As opposed to mere opinion, Mill goes on to acknowledge that freedom of action is more apt to stand in need of regulation where it infringes on the well being of the group. The remainder of On Liberty attempts to resolve the tensions arising from this natural conflict between the one and the many.

Implications for subsequent history. By formulating his theory of liberty apart from the Bible, Mill ironically joined a long train of philosophers whose collective efforts tended toward the enslavement of man in the 20th century. Utilitarianism has become perhaps the dominant strain in the political philosophies of the modern world. The editor’s Introduction to On Liberty admits that Mill’s “middle-class Liberalism was a halfway house between the Radical reform of the Benthamites and the Fabian reform of the Socialists.” Both species of humanism could draw inspiration from the utilitarian creed.

In spite of his insistence on liberty for the individual, Mill denounced the principles of democratic rule in Representative Government (1861), drawing heavily on the observations of Tocqueville.

“Liberty consists in doing what one desires”, wrote Mill(2). The historical outcome of this belief has been a clamor for unrestrained freedom or licentiousness, rather than a biblically regulated “liberty under law”. In spite of his call for individual liberty and his formal denial of socialism, Mill ended as an operational socialist. As a member of Parliament (1865-68) he supported public ownership of natural resources, compulsory education, and state-enforced charity. The problem with private charity, he maintained was that it functions “uncertainly and casually…(it) lavishes its bounty in one place, and leaves people to starve in another”(3). Thus the welfare state was invited in to set up its so-called safety net.

Biblical analysis. Mill is correct in arguing that the state has a legitimate interest in preventing one individual or group in society from harming another. This power extends even to economic activity as seen in Nehemiah’s command to the exploiting nobles of Jerusalem to “Restore, I pray you, to them, even this day, their lands, their vineyards, their olive yards, and their houses…that ye exact of them” (Neh. 5:12). Then, as if in response to Mill’s concern that the state aggrandize itself at the expense of its people, Nehemiah restrained himself from the public purse. “Moreover from the time that I was appointed to be their governor in the land of Judah…I and my brethren have not eaten the bread of the governor…because of the fear of God…because the bondage was heavy upon this people” (Neh. 5:14,15,18). “Because of the fear of God,” the state is to limit itself to the correction of injustice in society.

However, Mill’s theory breaks down under the weight of the question of who is to decide whether or not an action is contrary to the general interest. He cannot tell us definitively if it is the individual or society. Either answer leads ultimately to the destruction of the principle because neither will judge without prejudice. Moreover, he is skeptical of the rational capabilities of both the individual and the group. He preferred the “counsels and influence of a more highly gifted and instructed one or few.” (Ibid., p. 81). Apart from the controlling influence of Scripture, this points to the tyranny of Plato’s philosopher-kings.

Mill’s fundamental error lay in his rejection of the Bible as the final arbiter on questions of social and political conflict. He refers to the Old Testament as being “in many respects barbarous” (Ibid., p. 59). By holding out the hope of heaven and the threat of hell as motives to a virtuous life, Mill presumptuously declares that the Bible falls “far below the best of the ancients” (Ibid., p. 60). Furthermore, Mill informs us that the Bible is not a sufficient guide for life, contrary to II Timothy 3:16. “I think it a great error,” he intoned, “to persist in attempting to find in the Christian doctrine that complete rule for our guidance which its Author intended it to sanction and enforce, but only partially to provide. I believe that other ethics than any which can be evolved from exclusively Christian sources must exist side by side with Christian ethics to produce the moral regeneration of mankind” (Ibid., p. 62). Thus he rejected the only rule by which the freedom of the individual may be balanced with the legitimate interests of the state.

Corrective or Prescriptive Actions: There is much to learn from the father of John Stuart Mill (James) by way of positive and negative example. The elder Mill assumed responsibility for his son’s education at a very early age, refusing to leave it to his mother, to the state, or to any other third party. This included the study of Greek at age three, Latin at age eight, followed by reading in the classics and history. This is a direct rebuke to the many negligent fathers of the present day who insist on plundering their neighbors to pay for the education of their children. However, as a young adult, John Stuart felt no affection for his father, complaining that his stern focus on the intellectual had left no room for the cultivation of music, poetry, art or emotion. This too, is a lesson for fathers. Better to look to the example of Joseph, who focused on all facets of his Son’s development: “And Jesus increased in wisdom and stature, and in favour with God and man” (Lk. 2:52).